INTRODUCTION

Aquaculture remains a cornerstone of marine and fisheries production in Indonesia. Aquaculture activities, combining existing potential with the availability of promising technologies, can certainly support increased production. According to statistical data from the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia for 2022, the aquaculture production volume was 14,776,056.93 tons and increased to 16,967,518.25 tons in 2023 (Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024). Aquaculture in West Java contributes to Indonesia’s fish production. The area and production volume of still-water pond fish in West Java in 2023 amounted to 257,378,868 m2 with a production of 1,308,635 tons (Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024). Tasikmalaya City, with its aquaculture area and number of fish farmers, contributes to the increase in national fish production. The area and number of fish farmers in Tasikmalaya City in 2024 are shown in Table 1.

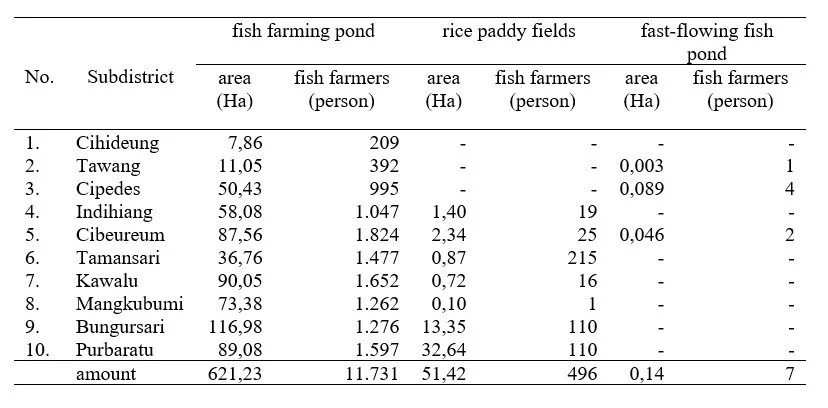

Table 1. Area and Number of Fish Farmers by Business Sector and District of Tasikmalaya City, 2024.

Source: Fishery Statistical Data, Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024

Table 1 shows that Tasikmalaya City has fisheries potential that can be developed sustainably. The area of grow-out fish ponds is 621.23 hectares with 11,731 fish farmers, rice-fish (sawah mina) paddy fields cover 51.42 hectares with 496 cultivators, and fast-flowing water ponds cover 0.14 hectares with 7 cultivators (Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024).

The fish production data in Tasikmalaya City for the past five years can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Graph of Fish Production Data for 2019-2023

Source: Fishery Statistical Data, Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024

In Figure 1, fish production in the City of Tasikmalaya over the past five years has experienced fluctuations. Fish production in 2023 decreased by 33.35 tons compared to 2022. This presents a challenge for fish farmers as well as the local government, in this case the Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries Security Office of Tasikmalaya City, to work harder to increase fish production by implementing or developing appropriate strategies to boost the fisheries output.

The fluctuations in fish production are influenced by productivity levels. Productivity data for still-water ponds in Tasikmalaya City were 1.49 kg/m2 in 2019, 1.50 kg/m2 in 2020, 1.50 kg/m2 in 2021, 1.44 kg/m2 in 2022, and 1.40 kg/m2 in 2023 (Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024). Based on the productivity of fish cultivation in still-water ponds, the average productivity in 2023 in Tasikmalaya City decreased compared with the previous year, 2022.

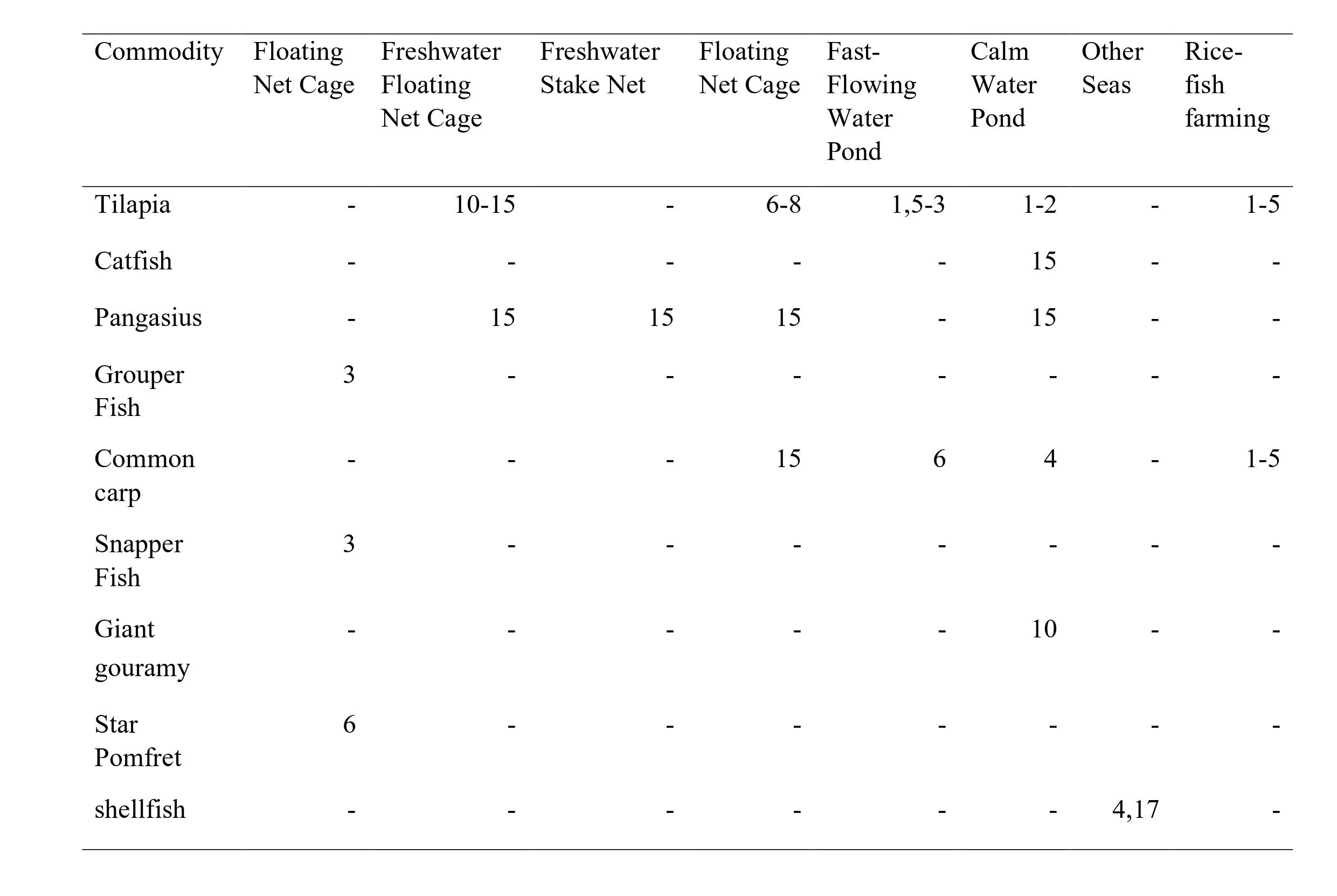

The average fish productivity in Tasikmalaya City, when compared to national fish productivity, is still below the standard. The national standards for aquaculture productivity can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. National Aquaculture Productivity Standards (kg/m2).

Source: Directorate General of Aquaculture, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024.

Comparison of productivity rates for several fish commodities in Tasikmalaya City with the national fish productivity standards according to the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia for fish farming in still-water ponds can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of Fish Commodity Productivity Rates in Tasikmalaya City in 2023 with the National Fish Commodity Productivity Standard (kg/m2)

Source: Directorate General of Aquaculture, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024; Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024.

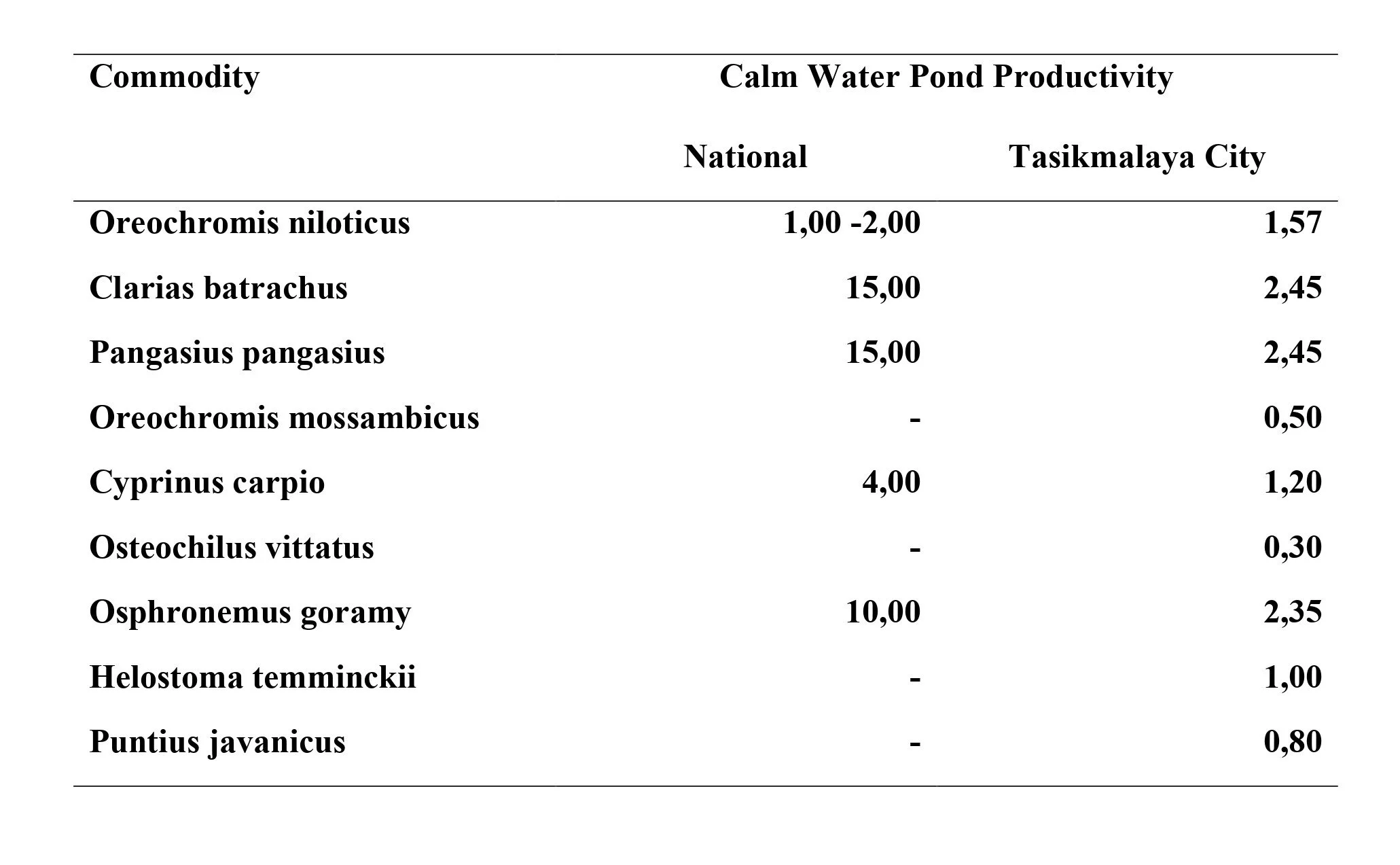

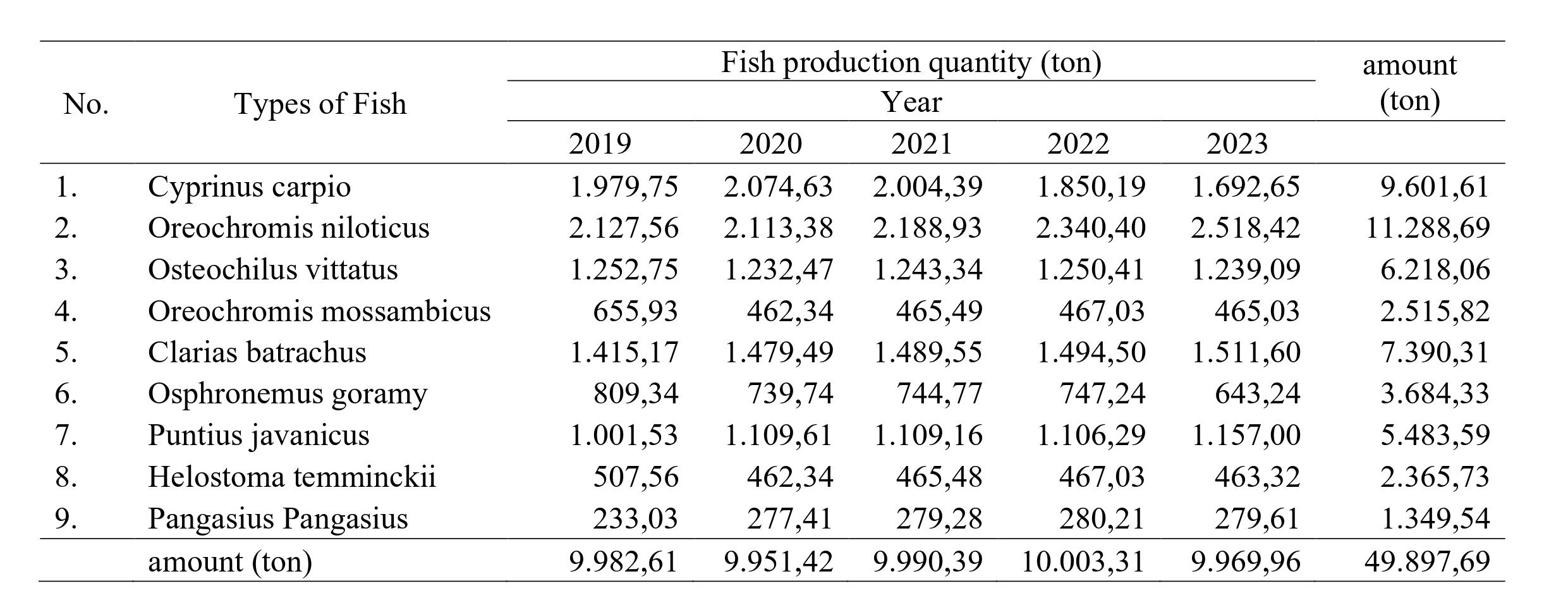

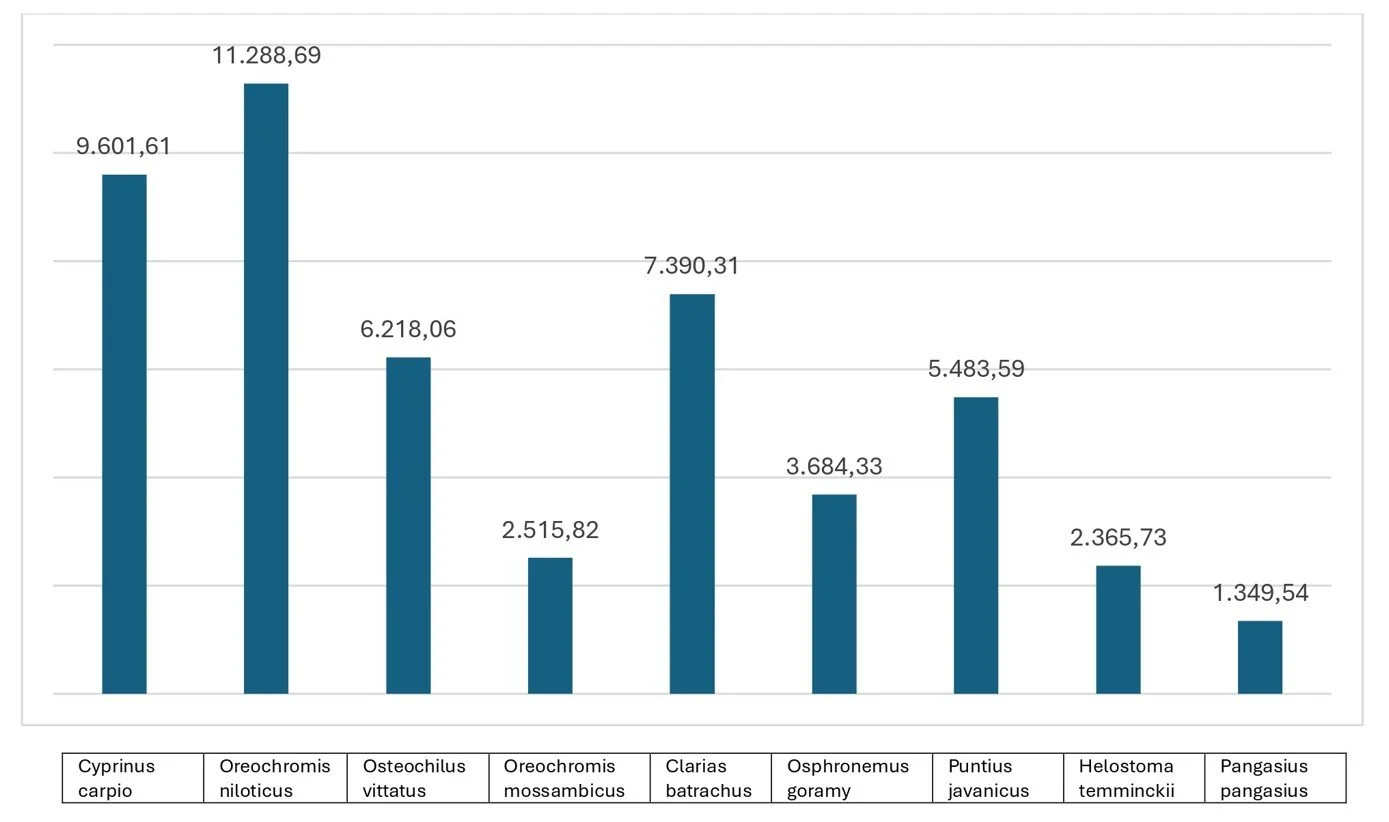

The fish production volume in Tasikmalaya City is derived from the production of freshwater fish commodities, namely Cyprinus carpio, Oreochromis niloticus, Osteochilus vittatus, Oreochromis mossambicus, Clarias batrachus, Osphronemus goramy, Puntius javanicus, Helostoma temminckii, and Pangasius pangasius. The production quantities for each fish species from 2019 to 2023 can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. Production Volume for Each Fish Species in the City of Tasikmalaya from 2019 to 2023

The fish species contributing the largest production is Oreochromis niloticus, with a production volume of 11,288.69 tons over the past five years, followed by Cyprinus carpio a production volume of 9,601.61 tons. The production chart for each fish species in Tasikmalaya City for the years 2019 through 2023 can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Source: Fishery Statistical Data, Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024

Figure 2. Fish Production from 2019 to 2023 (in tons).

Source: Fishery Statistical Data, Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries of Tasikmalaya City, 2024

Tilapia production contributes the largest share of total fish production compared to other fish species. Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is a freshwater fish that has been cultivated in many countries around the world, including Indonesia. This tilapia has many advantages and is easy to farm compared to other freshwater fish species. Tilapia can be cultivated in various waters—freshwater, brackish water, or the sea. It can be raised in different farming systems, tolerate low-oxygen stagnant water, respond well to formulated feed, and is easy to breed (Ghufran, 2013).

Tilapia farming is one of the productive aquaculture activities that can generate profits in the fisheries sector. However, in tilapia farming there are still various problems that need to be resolved to improve the success of tilapia culture. Problems or constraints commonly encountered in tilapia farming include inbreeding or mating between close relatives, which causes the quality of fry in subsequent generations to decline; dirty pond water, which can hinder or damage egg development; and uncontrolled reproduction because tilapia spawn easily (Saparinto, 2014).

In addition to aiming to increase production, fish farming activities also need to be environmentally aware and sustainable. The implementation of Good Fish Rearing Practices, hereinafter referred to as Good Aquaculture Practices, is the application of methods for rearing and/or growing fish and harvesting the results in a controlled environment so as to ensure quality and food safety from the cultivation by paying attention to sanitation, feed, and fish medications. (Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, 2024).

The application of Good Fish Farming Practices through quality management, food safety, fish health and welfare, environmental sustainability, and socio-economic considerations can increase fisheries productivity. According to Mendrofa and Zebua (2025) in their study, they discuss the technical, environmental, social, and economic aspects of Nile tilapia farming. The results show that government policy, fish stocking density, feed, and water quality all affect the productivity of Nile tilapia culture. The study offers recommendations to improve productivity through optimal environmental management, the use of appropriate technology, and supportive policies for farmers.

Aquaculture production generated by fish farmers is expected to remain sustainable and produce safe-to-consume products while being environmentally conscious. Environmentally aware and sustainable aquaculture activities are part of the characteristics of the Green Economy. According to Purwanto (2024), the Green Economy emphasizes sustainable and inclusive economic growth that does not sacrifice the environment or natural resources for short-term gains.

The green economy needs to be developed for several important reasons, namely: the green economy seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants; increase the use of renewable energy by reducing dependence on fossil fuels; protect biodiversity and natural ecosystems; promote the creation of sustainable and equitable green jobs; foster green innovation and investment; establish policy frameworks that support the green economy (supportive public policies); enhance resilience to the impacts of climate change; ensure social justice and equity; and, finally, encourage responsible consumption and production (Purwanto, 2024).

According to Arisandi et al. (2023), the development of fishery product innovations based on the green economy concept needs to be carried out. Their research on fish farming states that fishery product innovations grounded in the green economy can produce fish products that increase fish weight, increase fish length, and enhance fish immunity; by producing these aquaculture products, the productivity outcomes of fish farming will be indirectly increased.

Green economy can be understood as Good Aquaculture Practices (GAP/CBIB) because there are similarities between the application of GAP and the characteristics of the Green Economy (Appendix 1), namely an emphasis on sustainability and environmental awareness. The implementation of Good Aquaculture Practices according to the Regulation of the Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia (2024) is divided into four areas: food quality and safety, fish health and welfare, environmental conservation, and socio-economics. The application of the green economy in aquaculture is carried out by rearing, raising, and/or breeding fish and harvesting the products, realized through sustainable and environmentally friendly activities supported by Good Aquaculture Practices (GAP) certification.

According to Yulisti et al. (2021), in Indonesia, the Good Fish Farming Practices (CBIB) certification is one of the aquaculture certifications introduced by the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (KKP) aimed at improving aquaculture management, promoting sustainability, environmental protection, social responsibility, and disease management. According to Wigiani, as cited by Wafi et al. (2024), in addition to establishing profitable operational farming standards, CBIB also aims to create sustainable and environmentally friendly farming practices.

In line with the development of aquaculture activities in Tasikmalaya City, the current field situation is that the implementation of the green economy is limited to the use of cultivation facilities and infrastructure, such as using organic fertilizers, using certified seeds, employing simple cultivation equipment that is safe and not prone to rust, using environmentally friendly farming equipment that generally does not rely on fossil-fuel–powered devices, and using feeds and medicines that are safe for fish health.

The increase in fishery production currently faces several problems that need to be solved. According to the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Regulation Number 17 (2020), the challenges for increasing marine and fisheries production include the following:

a. Aquaculture business activities in Indonesia are still dominated by small-scale farmers, traditional technologies, low productivity, declining water and environmental carrying capacity, impacts of climate change, relatively low added value, suboptimal land use, and high production costs;

b. Unstable availability of raw materials to support marine and fisheries industrialization;

c. Access to capital for scaling up business operations;

d. Competitiveness and quality of fishery products for export that still need improvement;

e. Supporting infrastructure in regions is not yet fully adequate, such as fishing ports, hatchery centers, salt ponds, fish farming facilities, and others; and

f. Ecosystem degradation, climate change, and extreme weather.

Meanwhile, other challenges in the management of marine and fisheries resources, according to the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Regulation No. 17 (2020), include the suboptimal implementation of Good Fish Farming Practices (CBIB) in aquaculture activities, limited availability and distribution of superior and high-quality broodstock and fry, high feed prices that lead to inefficient production costs, disease, human resource capacity, inadequate and limited infrastructure to support aquaculture business such as fish hatcheries, irrigation channels, electricity, access roads for production, fish health laboratories, and tissue culture laboratories.

Aquaculture in Tasikmalaya City faces common problems in the management and implementation of good fish farming practices. Judging by the number of fish farmers in Tasikmalaya City, many fish farming businesses have still not applied the principles of Good Fish Farming Practices (CBIB). According to data from the Tasikmalaya City Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Office, the number of fisheries enterprises holding a Good Fish Farming Practices (CBIB) certificate in 2023 in Tasikmalaya City was only 20 fish farming businesses. The number of certified fish farmers under the Good Fish Farming Practices (CBIB) in Tasikmalaya City can be seen in Appendix 3.

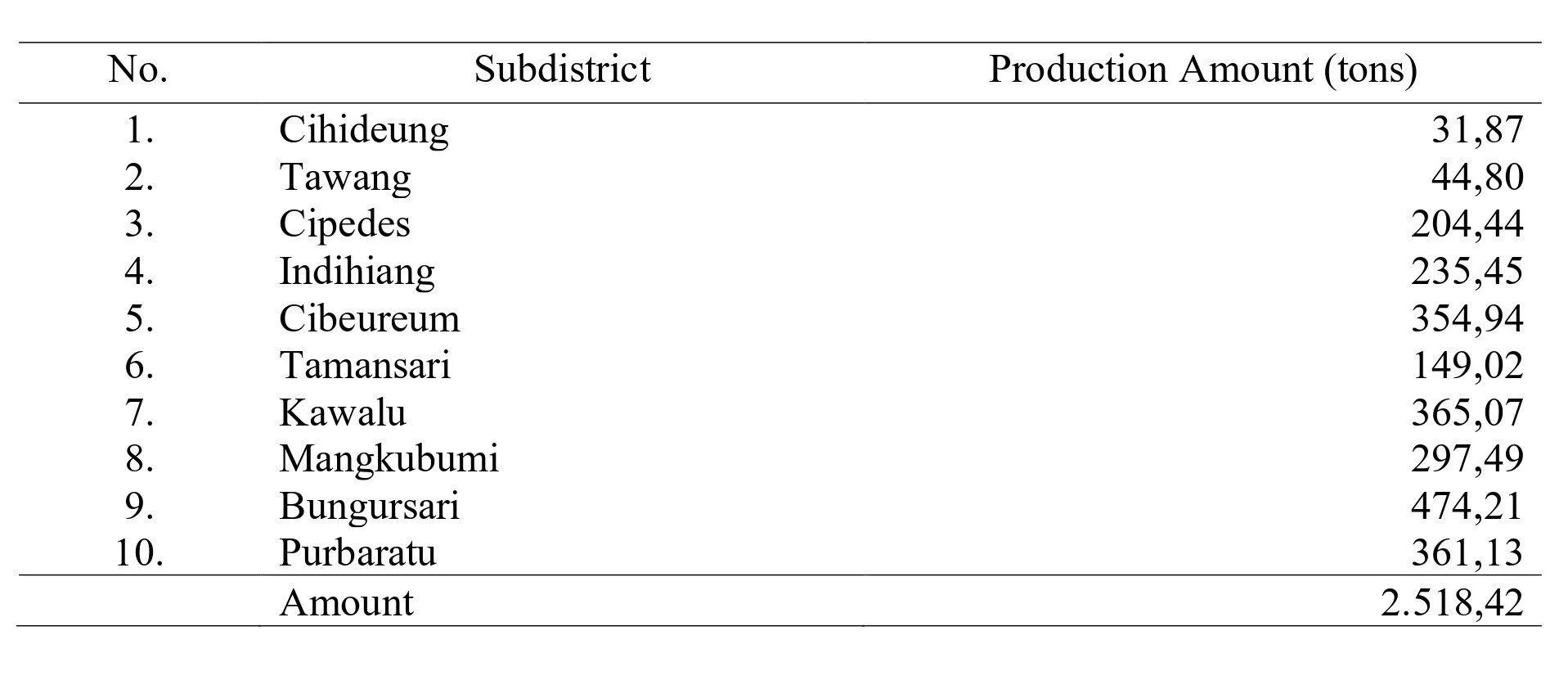

In supporting the strategy for developing tilapia farming based on a green economy, it is necessary to be supported by a research location that can accurately represent the actual conditions of tilapia cultivation. According to 2023 statistical data, the largest tilapia production was in Bungursari District, with a production volume of 474.21 tons (Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries, Tasikmalaya City, 2024). Tilapia production data in Tasikmalaya City can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5. Tilapia Aquaculture Production by District in Tasikmalaya City in 2023.

Source: Department of Food Security, Agriculture and Fisheries, Tasikmalaya City, 2024

The city of Tasikmalaya has a fisheries area located in an economically strategic zone known as the Minapolitan Area. In addition to the city of Tasikmalaya, other regencies and cities in the West Java region have been designated as Minapolitan Aquaculture Areas. Those regencies and cities are Bogor Regency, Indramayu Regency, Subang Regency, Garut Regency, Sukabumi Regency, Cirebon City, and Karawang Regency (Decree of the Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia, No. 35 of 2013).

Bungursari District is a district in the City of Tasikmalaya that has significant potential for fish farming land. This district contributes the highest fish production in the City of Tasikmalaya. The Bungursari area has been designated as a fisheries zone under Tasikmalaya City Regional Regulation No. 4 of 2012 as a Minapolitan Area together with Indihiang District.

Tilapia farming with good productivity can increase the quantity of harvested fish, thereby contributing to a rise in overall fish production. This tilapia aquaculture is expected to be environmentally conscious and sustainable. This presents a challenge that needs attention; therefore, the author is interested in conducting research on development strategies for tilapia farming based on the green economy in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

Problem Statement

Based on the background and the problem formulation above, the issues in this study can be identified as follows:

What internal environmental factors constitute the strengths and weaknesses in the development of green economy-based Nile tilapia farming in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City?

What external environmental factors constitute the opportunities and threats in the development of green economy-based Nile tilapia farming in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City?

What are the alternative strategies for developing green economy-based Nile tilapia farming in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City?

Which strategy priorities can be applied to the development of green economy-based Nile tilapia farming in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City?

Research Objectives

Based on the problem statements above, the objectives of this study are:

To identify internal environmental factors (strengths and weaknesses) in the development of green economy-based tilapia aquaculture in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

To identify external environmental factors (opportunities and threats) in the development of green economy-based tilapia aquaculture in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

To develop alternative strategies for the development of green economy-based tilapia aquaculture in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

To determine priority strategies that can be implemented in the development of green economy-based tilapia aquaculture in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

Benefits of the Research

The results of the research are expected to have the following benefits:

As additional knowledge and an increased understanding for researchers in the field of aquaculture, specifically regarding strategies for developing aquaculture based on the green economy in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

As input for fish farmers in determining development strategies for aquaculture within their business environment.

As input for the government in formulating policies to support the development of green-economy-based aquaculture strategies in the Minapolitan Area of Tasikmalaya City.

This research is expected to serve as a reference for other authors who will conduct similar studies in the future.